Note: I am working on a libretto right now, and the best way to learn to write something new is to study examples. I thought it might be interesting for you to watch the process of learning a new art form, and then, when my libretto is done, perhaps someone will do a close reading of it and see if it’s successful!

In this series, I give a brief history of an opera (with a link to a synopsis) and then share some of my observations about the libretto. What I’m looking for is dramatic force: when and how does a libretto provide the dramatic force to sustain an opera and to inspire a composer? What themes are particularly suited to opera? I’m also interested in pacing: how much story can a libretto reasonably hope to tell? I’m not primarily interested in commenting on the music, though of course some musical observations will arise in my close look at the words.

Nosferatu is a famous tale, famous long before Robert Egger’s star-studded remake came out last year. Like many of the operas I’ve been studying, the story is one that great artists keep coming back to; there is something at the heart of this tale that continues to draw us in.

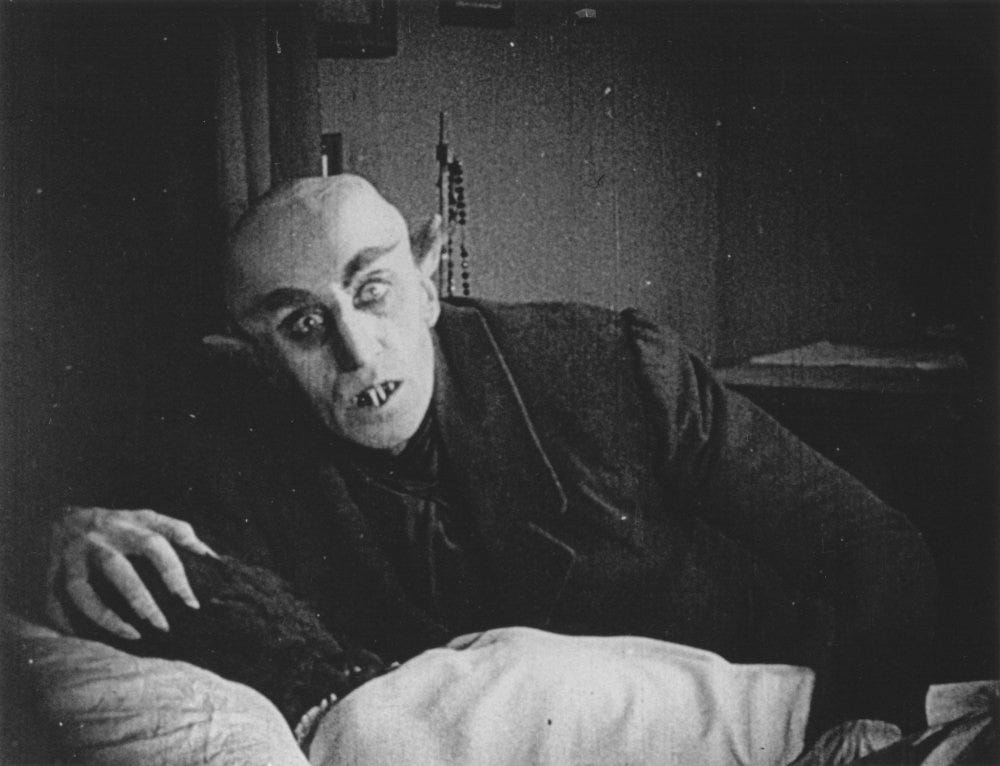

It is, of course, a vampire story. This is the first libretto I’ve read that retells a story that began not as a book or a play or a traditional tale, but a film. Nosferatu is based on the 1922 German silent film of the same name, directed by F.W. Murnau.

The film (synopsis here) came out just ten years after Bram Stoker’s death, and when Stoker’s widow sued the studio for violation of copyright, nearly all copies of Nosferatu were destroyed. That didn’t keep it from becoming a classic. Indeed, Nosferatu was genre-making; it has been called the first horror movie, and I suppose that makes Gioia’s libretto the first “horror opera” I’ve reviewed here.

It’s difficult to track down a synopsis of the opera. In its major events, it follows the arc of Murnau’s film, so I recommend reading up on that. There are a few significant differences between the film and the libretto that we’ll get into below.

~~~

Gioia’s libretto (available for purchase here, in a beautiful volume from Graywolf Press) is remarkable for a few reasons. First of all, it’s a creative coup de grace to take a silent film and reimagine it as an opera with poignant, memorable lyrics. The libretto is a masterwork of poetry; it stands alone as a noteworthy piece of art. (See here for an interview Gioia gave on Nosferatu and the connection between poetry and performance.) The verse is elegant and thoughtfully paced, with moments of incandescence. I love the idea of overlaying the plot and images of a silent film like Murnau’s with verse.

But the libretto is no mere recounting of a familiar tale. Gioia makes a few tiny changes to the emotional weft of the story, and as a result, the psychological and spiritual pattern he weaves is distinct from both the original Dracula material and Murnau’s film. It is a wonderful example of how an opera’s libretto works: by identifying key moments of emotional, spiritual, and/or relational tension and showing how those moments, which may be mere instants in chronological time, exert a defining (potentially destructive) force on the rest of our lives.

Opera offers us a glimpse at the back of the tapestry, if you will, where we can see the knots that hold the pattern of our lives together, big, bulky things that define the shapes we see on a daily basis. It introduces us to a new spiritual and emotional economy, in which tiny decisions are immensely valuable and a passing doubt or dalliance with evil can become the gravitational center of our lives. Operas do not unfold in a normal, chronological way. Rather, they spring from moment to moment, bypassing days and weeks and months and even years, to show us how key moments in our lives build on each other and lead to a climax.

In that way, Nosferatu is ideal operatic fare. The story is a bit of a Dracula-in-miniature, but the two tales are quite markedly different in tone. Gone are the intrepid vampire-hunters, the seductive undead brides, the courtly and engaging vampiric villain, the dense and action-packed plot. In Nosferatu, the monster (now known as Count Orlock) is a living horror, a physical wreck whose appearance repulses others. There are no bold Americans, no crafty scholars of vampire lore, no wealthy fiances to go toe-to-toe with pure wickedness. There is no swashbuckling quest. There are simply ordinary people dealing with the ordinary difficulties of life—financial problems, career problems, health problems, marriage problems—all brought to a crisis because of a not-at-all-ordinary difficulty: an obsessive vampire.

Nosferatu is less of a spectacle than Dracula, but it is more terrifying; it pits decency against evil and shows just how insufficient decency is against primal darkness. The only thing, Nosferatu argues, that can overcome soul-sucking evil is self-sacrifice—to the point of death. That kind of sacrifice is a perfect operatic theme, because it creates plot moments in which the characters step outside of time to reflect on their own lives and souls. It is this timelessness, this springing from crucial instant to crucial instant, that Gioia recognized in Murnau’s film and beautifully rendered into poetry.

~~~

I want to talk about that poetry, but first, we need to explore some of the subtle differences between Nosferatu the film and Nosferatu the opera. Gioia follows the film’s plot quite closely in terms of major happenings: both open in the city of Wisborg, where the corrupt estate agent (Herr Knock in the film, Herr Skuller in the opera) sends his somewhat hapless new employee (Thomas Hutter in the film, Eric in the opera) to a client’s castle in the dark heart of central Europe to finalize a business deal. The client is, of course, Count Orlock, a vampire who believes he is predestined to be with Hutter’s wife, Ellen. Orlock attacks Hutter, leaving him wounded, and sets off on a ship loaded with coffins and plague-ridden rats to Wisborg in search of Ellen. Upon landing, Orlock unleashes the plague and calls to Ellen, who resists his summons. She learns of a way to defeat Orlock: a woman must keep a vampire with her until dawn, when the sun’s rays will turn the vampire into dust. Desperate to put an end to the suffering, Ellen decides to allow Orlock into her bedroom and try to destroy him. Her ploy succeeds, but she dies in the process.

This is the basic plot of both the film and the opera, but Gioia draws out nuances of the main characters, particularly the young husband and wife, to shift the story’s themes. The young Herr Hutter is always a bit of a weak character. Lured into the vampire’s castle, he cannot rouse himself to flee, but inexplicably lingers until his fate is sealed. Gioia expounds on this character. His Eric Hutter is more complex than Murnau’s Thomas; Eric is simultaneously more decent and more vulnerable than Thomas. He is youthful, earnest, immature, sincere—no match for the machinations of an ancient evil. He expresses his despair at his inability to find a solid career and care for his beloved wife in poignant terms, making him an easy mark for Herr Skuller.

One of the biggest changes from the film is the way Orlock becomes aware of Ellen, triggering his fatal obsession. In the film, he comes across her portrait by accident, finding it among in Thomas’ possessions. In the opera, however, Eric insists on showing it to him, thrusting it under his eyes until Orlock pays attention to it. Eric’s love for Ellen is real, yes, but it is immature. He loves her, but he cannot provide for her. He is proud of her, but he cannot protect her from evil. In fact, his lack of cunning puts not only her soul, but her life in danger. Against primal evil, decency is not enough.

In another shift from the film, Gioia’s Ellen is drawn with much more psychological depth. She is not merely a virtuous woman besieged by darkness. She is a complex, fully realized heroine whose battle is against the darkness in her own soul as much as against Orlock. Ellen, in this telling, is no pale Gothic lady. She is a full-blooded human being with visions, dreams, and desires. All of that makes her particularly vulnerable to Orlock’s temptations, but it also makes her uniquely prepared with the courage, intelligence, and cunning to lure him to his destruction.

In Gioia’s hands, this Gothic horror tale retains its otherworldiness but gains a new element by shaking off the easy narrative of fate. Evil is not an unconquerable force. The tragedies here are not determined. Ellen’s death is not unavoidable. It comes about as a result of human pride and frailty, but also from a heroic choice to test the powers of good against evil.

~~~

Nosferatu (which, for the rest of this post) refers to the opera, not the film) is written in English verse. That verse is characteristically clean and clear. One of Gioia’s greatest poetic strengths, evident in his shorter lyric poems and on full display here in libretto form, is his clarity. He is a poet of stark images and clean lines; no rococo flourishes here. The crystalline language makes for arias as plaintive as lullabies, like this one in which the corrupt Skuller advises the young husband Eric to join his business:

Never imagine the world will provide Shoes for your children or a bed for your bride, Bread for the table, a roof for the rain. Turn away troubles, and they come again. Whatever you love is easily lost. A man must be strong whatever the cost.

These lines could stand alone as a complete poem. They are stark, unelaborate, and as a result, piercing. There’s no unnecessary flourishing about here with the rapier; Gioia goes straight for the kill, as in this chilling aria sung by Nosferatu to Ellen:

I am the image that darkens your glass, The shadow that falls wherever you pass. I am the dream you cannot forget, The face you remember without having met. I am the truth that must not be spoken, The midnight vow that cannot be broken. I am the bell that tolls out the hours, I am the fire that warms and devours. I am the hunger that you have denied, The ache of desire piercing your side. I am the sin you have never confessed, The forbidden hand caressing your breast. You've heard me inside you speak in your dreams, Sigh in the ocean, whisper in streams. I am the future you crave and you fear. You know what I bring. Now I am here.

The language here is representative of the libretto as a whole: everyday words joined in straightforward syntax, no veiling of the horror in misty description or shadowy hints.

Gioia runs a serious risk here. Everyone knows that horror works best when left to the imagination; once the monster is seen, it’s less frightening. Gioia argues, through his libretto, that this isn’t necessarily true. Unseen monsters are dreadful, yes, but coming face to face with evil does not strip it of its horror. Rather, the very simplicity of it, the starkness with which it demands our whole souls, the utterness of the darkness confronting us, is even worse than the terrors of our imaginations.

One of the loveliest passages in the libretto is Act II, Scene 2, where the plague is sweeping through Wisborg. Ellen sings about evil and doom against a Chorus chanting the “Dies Irae” from the traditional Catholic funeral Rites. Later in Scene 3, Ellen braces herself for the coming confrontation with Orlock by singing the “Salve Regina,” at first in Latin but later in her own translation that contains such curious lines as:

Salve, Maria,

Mother of misery,

Mother of mercy,

Save me from evil.

Trapped and defenseless,

I reach for your grace.

But I see only darkness,

And death's graven face.Her prayer becomes broken cries, “Salve, Regina, Mater…/Ad te clamamus… filia./He is climbing the stairs!/Mater Maria… Mater… Mater!” And her prayers are answered in the form of resolution and spiritual courage.

Now comes the test of justice. Holy Virgin, help me send Death himself down to the dead.

With these lines, Gioia lifts the classic vampire tale out of its Gothic setting and grafts it directly into the biblical battle between the Virgin and the serpent, a battle won through the Virgin’s fiat, which brings about the Incarnation. Orlock wants not just Ellen’s blood; he craves her soul, and with it, the soul of humanity itself. He is Nothingness itself, the void that is evil, the absolute rejection and negation of Goodness. Orlock introduces himself in “I am” statements, like those above in his song to Ellen and these eerie lines addressed to Eric:

I am the past that feeds on the present. I am the darkness that daylight denies. I am the sins that you must inherit-- The final truth in a world full of lies. I am the name that cannot be said. I am eternal, unliving, undead.

Orlock mocks God’s own identification as “I am” both in Exodus and in the Gospels. He asserts that he is what actually is, and that the basis of reality is not God’s creative, life-giving light, but destructive, consuming, darkness. Rather than the classic Augustinian assertion that evil is the absence of good, Orlock claims that any goodness in the world is merely the absense of evil, and evil is on its way to consume that goodness with its mere presence.

And, for most of the opera, it seems like he is right. Orlock, evil incarnate, seems irresistable. Merely by entering a room, he sucks the vitality out of goodness. By docking a ship, he brings plague and death to a whole city. He destroys a decent man and murders a heroic woman. He wrecks marriages and lives and endangers souls (in the case of Skuller, it seems likely that he damns souls).

But at the end, Ellen succeeds. She entices Orlock into staying with her until dawn, and then with her dying breath she flings open the curtain and lets a single ray of light fall on him. She perishes, but so does Orlock. Confronted with the light, he is destroyed. there is no lasting vital force here. Evil, brought face-to-face with goodness by Ellen’s heroic self-sacrifice, proves that it is a nothing, easily swept away by just a ray of light.

~~~

I could write much more about this libretto. It is a magnificent accomplishment, in the Aristotelian sense: it is a grand project, undertaken with courage and breadth of soul. Through it, Gioia takes the very best of vampire tales and creates a psychologically believable, emotionally gripping tale of good vs. evil that transcends its origins. It’s wonderful to me that a silent film could have given birth to such glorious words. The libretto offers a brilliant example of how to tell an epic tale in clean, disciplined, highly readable English verse.

@Sally Thomas @Joseph Bottum parts of this opera might actually be neat to feature on Poems Ancient and Modern.

This was very interesting - I study comparative literature, and I’m especially interested in operatic texts. I would love to read your libretto (and maybe write a paper on it) when it’s finished!